It’s increasingly hard to ignore the buzz surrounding driverless cars. Tesla and Google/Waymo are at the front of the pack, logging hundreds of thousands of driverless miles on the roads of California. If you believe the hype, then our roads are set to be transformed by the arrival of smoothly driving, congestion-busting, safety-enhancing autonomous vehicles.

Who stands to gain from driverless cars?

Why do people care so much about driverless cars? The average American drives for almost 300 hours a year, clocking up 10’000 miles. In the UK it’s even bleaker; the average individual spends more time driving than socialising, with an average of around 525 hours a year. Having a driverless car will win these hapless commuters over an hour a day, not to mention saving them the stress of actually operating a vehicle.

What will we do with this freshly-found time? We could choose to spend it on any number of pursuits: practicing embroidery, reading Shakespeare, or learning to play the jazz flute. I suspect, however, that we will choose to spend it the way we spend most of the rest of our leisure time: looking at a screen.

The great attention robbery

Companies such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter want you to spend as much time using their services as possible. As noted by Tristan Harris (‘the closest thing Silicon Valley has to a conscience’), these companies optimise to grab your attention, and keep it. The internet increasingly rests upon an advertising-driven business model: provide something addictive and free, then make money from advertising. Such a model is sustained by the eyeballs of the internet’s users. It’s not malevolent, it’s simply the model. The more time you spend on their websites or in their apps, the greater the profits, and the profits are great: $5.1 billion per quarter for Google, and $1.5bn for Facebook.

The idea of a whole new hour of distraction-free, completely static, socially isolated slice of time must have internet companies slavering. A passenger in a driverless car is a perfect consumer of screen-based entertainment. They’re sitting still and they can’t wander off. They have internet access and the ability to charge their device; in fact, driverless cars will no doubt come equipped with plush touch screens. And passengers will often be on their own, without the inconvenience of actual people to interfere with their social networking.

Perhaps this is part of the reason that driverless car talent is such hot property that top robotics universities can’t hold onto their students any more, why Uber and Google are currently brawling over IP in the area, and why Tesla’s reputation as a manufacture of electric vehicles is rapidly being eclipsed by its focus upon driverless technology. The company who wins doesn’t merely get to sell you a car: it gets access to your time, with which to sell you countless other things.

Radio ga ga?

Today, 96% of us have radios in our cars. But how many people would listen to the radio when they could instead safely watch a film, play a game, or go online? People have heralded the death of radio before, and Freddy Mercury’s worse fears haven’t come true yet. But driverless cars won’t need radios, because they’ll have everything else: just as mobile phones heralded the end of the home phone, the all-singing-all-dancing-connected-driverless-car will be very bad news for radio.

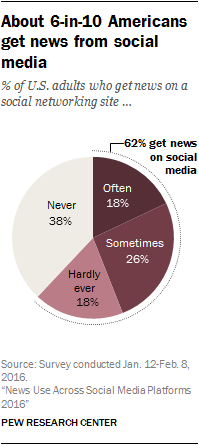

This is worrying because radio is a relatively legitimate and high quality source of information. Like newspapers, radio broadcasts (at least in Britain) are regulated and vetted for veracity. Fake news thrives far more on your Facebook feed than it does on the airwaves. The news that wins on Facebook is not the news that is most meticulously researched, the most incisively investigated, or the most searingly honest. It’s the news that make people click. 62% of Americans already get their news from social media: increasing this number is not good if you value diligent journalism or an informed public.

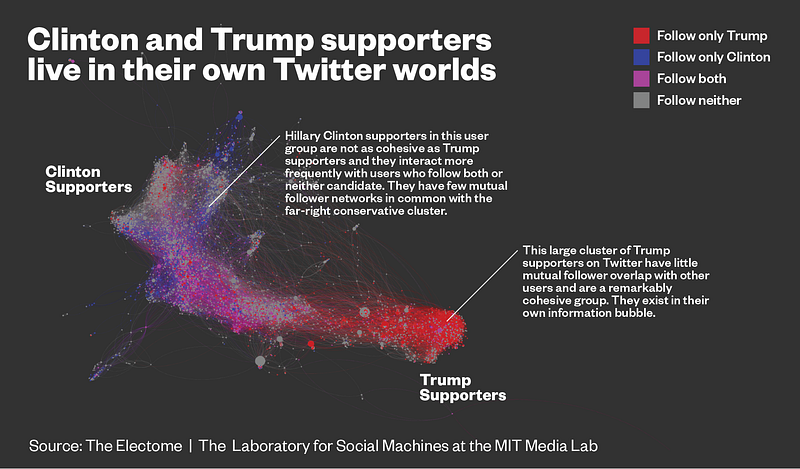

Furthermore, radio is a brilliant medium for debate and discussion (enjoy this clip of Nigel Farage being foxed by a clever caller). Conversely, Facebook and Twitter are wonderful places to meet people who have the same opinion as you. This limited and self-reinforcing consumption of media obscures our view of reality and helps form viciously partisan in-groups of the kind which are probably unhelpful. Less radio means more echo chamber.

Other thoughts

There are lots of other potential outcomes which I don’t have space to discuss in any depth. The environmental impact could be very positive or very negative, according to this recent report from the Department of Energy. If people use their cars more and they drive them faster, that’s bad; but if people share cars to offset the cost and are driven in a very effective manner by a fuel-saving algorithm, that could be good. Furthermore, if driverless cars make long-distance car travel more enjoyable, then perhaps it will cut down on short-haul flights, which would have an environmental upside.

There’s also a very interesting discussion to be had about where car data goes. Tesla have already stolen a march on the competition by using data produced by the owners of its cars to improve their products. The insides of driverless cars could also be rigged so as to provide other kinds of data: high quality speech recordings, for instance, could be a valuable byproduct of driverless cars, which could then be funneled into further improving vocal recognition and production software, opening the door to new realms of automation.